Logika: Programming Logics

1. Introduction: Why bother?

1. Introduction: Why bother?¶

That’s a good question! After all, you can hack a spreadsheet program or build an interactive game by writing a lot of code, experimenting with it, and patching it. After awhile, the program you wrote does more or less what you wanted.

But imagine if the rest of the world worked that same way – would you want to drive a car or fly an airplane that was “hacked together”? How about travelling in a bus across a bridge that fell down a few times already and was repeatedly patched till it (seemed) to hold?

Perhaps these analogies are a bit extreme, but professional scientists and engineers rely on planning, design, and calculation so that they are certain the products they want to build will work before anyone starts building them. Professionals rely on an intellectual foundation to plan, design, and calculate. For example:

physicists use mathematics as the intellectual foundation of their products

chemical engineers use chemistry

mechanical engineers use physics

computer engineers and computer (software) scientists use algebra and symbolic logic

If you develop significant expertise in software engineering, perhaps you will work at a firm or lab that develops safety-critical software, that is, software upon which people’s money or safety or lives depend. (An example is the flight-control software that lives in a jet. Another example is the navigation software in a satellite that talks to the GPS device in someone’s car.) Software of this nature has to be working correctly from the beginning – there is no freedom to hack-and-patch the code once it is in use. Software engineers must use algebra and logic to plan and calculate how the software will behave before the software is built and installed.

This story is not an idle one: As you probably know, computer processor chips are planned out in a programming language that looks a lot like C. When Intel designed its first Pentium chip, there was a programming error in one of the chip’s coded hash tables. The coding was burned into hardware, and millions of chips were manufactured. The error was quickly detected – the chip did not always perform multiplication correctly. As a result, Intel lost a lot of money recalling the faulty chips and manufacturing a patched replacement. These days, Intel uses techniques for validating chip designs much like the ones you will learn in this course.

If you have taken a software architecture course (e.g., CIS 501: Software Architecture and Design), you know that large systems can be drawn out, or “blueprinted,” with diagrams that show the components and how they connect together by means of method calls, event broadcast, and message passing. What we will learn in this course is lower level and more basic – we will learn how to calculate how the lines of coding in each component compute internal knowledge as they convert inputs into outputs.

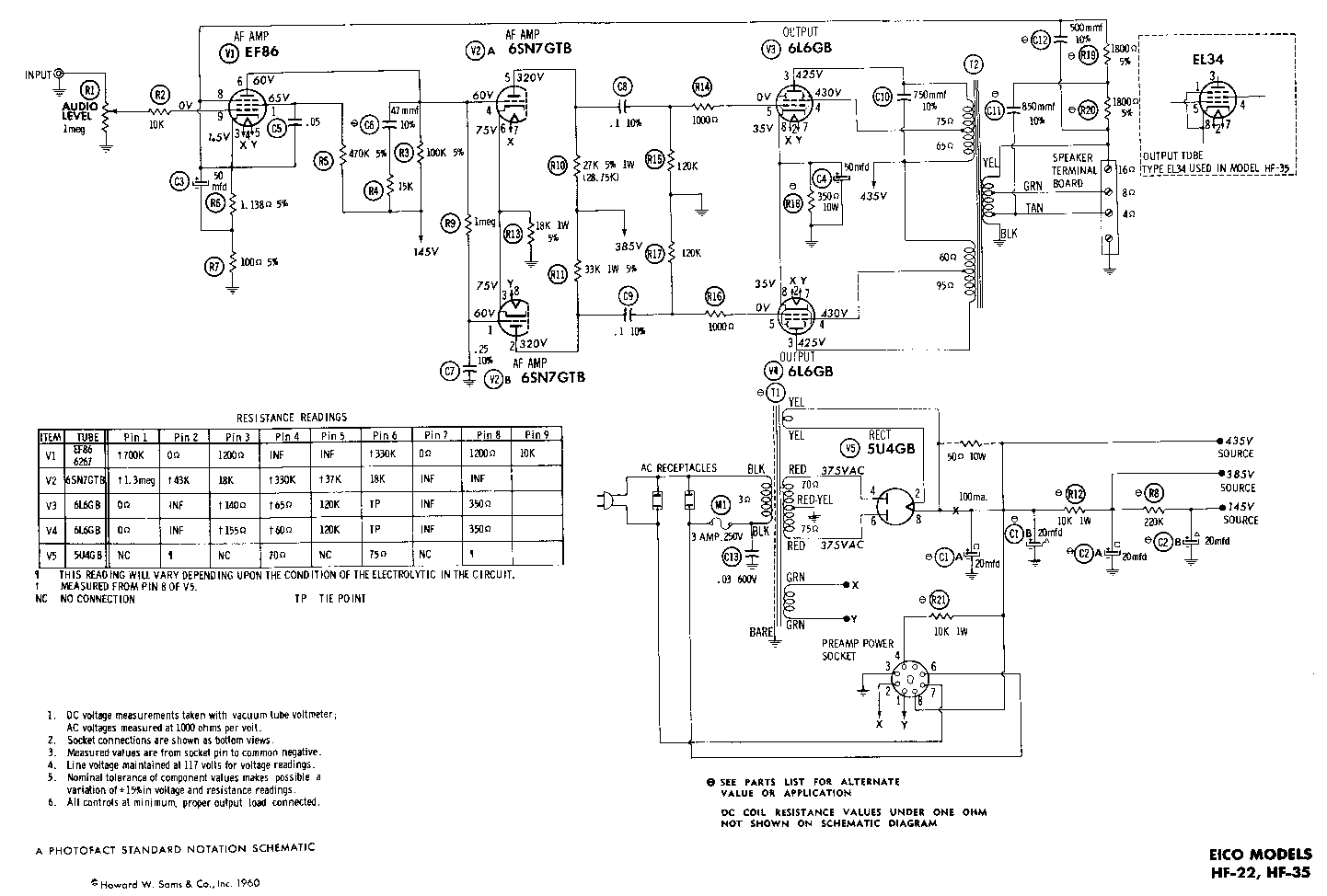

To understand the idea, let’s think about electronics. When an electronic device, like a TV-set or radio, is designed, the parts of the device and their wirings are drawn out in a diagram called a schematic. Here is a schematic of a vacuum-tube guitar amplifier, the kind used by recording studios to produce a warm sound with good sustain:

Notice that the wires to the vacuum tubes (the globes labelled V1 through V5) are labelled with voltages, and there is a table in the lower left corner of the schematic that lists the correct resistances that will hold at each of the wires (“pins”) that connect to the tubes.

The voltage and resistance calculations are both an analysis and a prediction of how the circuit should behave. The numbers were calculated with mathematics and algebra, and if the electronics parts are working correctly, then these voltage, amperage, and resistance levels must occur – the foundations of electronics (math and algebra) demand it.

When the circuit is built, the actual levels are measured with a multimeter and compared to the calculations; if there is a discrepency, this is a signal that some part within the circuit is faulty.

A computer program is a “circuit” that “runs on” knowledge, and when we design the parts (lines) of a computer program, we should include “knowledge checks” that assert the amount of knowledge computed by the program at various points. We will learn how to write and insert such knowledge checks, called assertions, into programs and use the laws of symbolic logic to prove that the assertions will hold true.

You will see many examples of “program schematics” in the upcoming chapters. Here are two. First, this little code fragment apparently selects the larger of two integers and prints it:

1import org.sireum.logika._

2// the above imports, for example, type Z,

3// which is an arbitrary-precision integer type (i.e., scala.BigInt)

4

5val x: Z = readInt() // readInt asks an integer from the user via console input

6val y: Z = readInt() // val declares a read-only variable

7var max: Z = 0 // var declares a read/write variable

8if (x > y) {

9 max = x

10} else {

11 max = y

12}

13println("Maximum of ", x, " and ", y, " is ", max, ".")

Think of the program as a “circuit” whose lines are “wired” together in

sequence.

Instead of voltage, information or knowledge “flows” from one line to the next.

Here is the program’s “schematic” where the internal “knowledge levels” are

written in symbolic logic and are inserted within the lines of the program,

enclosed by set braces, l"""{ ... }""":

3val x: Z = readInt()

4val y: Z = readInt()

5var max: Z = 0

6if (x > y) {

7 l"""{ 1. x > y premise }"""

8 max = x

9 l"""{ 1. x > y premise

10 2. max == x premise

11 3. max ≥ x algebra 2

12 4. max ≥ y algebra 1 3

13 5. max ≥ x ∧ max ≥ y ∧i 3 4 }"""

14} else {

15 l"""{ 1. ¬(x > y) premise

16 2. y ≥ x algebra 1 }"""

17 max = y

18 l"""{ 1. max == y premise

19 2. y ≥ x premise

20 3. max ≥ y algebra 1

21 4. max ≥ x algebra 1 2

22 5. max ≥ x ∧ max ≥ y ∧i 4 3 }"""

23}

24l"""{ 1. max ≥ x ∧ max ≥ y premise }"""

25println("Maximum of ", x, " and ", y, " is ", max, ".")

The last annotation, l"""{ ... max >= x ∧ max >= y ... }""", is a symbolic-logic

statement that max is guaranteed to be greater-or-equal to both inputs.

We now know, once the program is implemented, it will behave with this logical

property.

Here is a second example, a complete analysis of a function that squares all the integers in an array that is passed to it as its argument:

3// Updates parameter a, which is of type array of integers (ZS),

4// in place so that each of its ints are squared

5def square(a: ZS): Unit = {

6 l"""{ modifies a

7 post ∀i: (0 ..< a.size) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i) }"""

8

9 l"""{ 1. a == a_in premise }"""

10

11 var x: Z = 0

12

13 l"""{ 1. a == a_in premise

14 2. x == 0 premise

15 3. 0 ≤ x algebra 2

16 4. 0 ≤ a.size algebra

17 5. x ≤ a.size subst2 2 4

18 6. {

19 7. j: Z

20 8. {

21 9. 0 ≤ j ∧ j < x assume

22 10. 0 ≤ j ∧e1 9

23 11. j < x ∧e2 9

24 12. ⊥ algebra 10 11 2

25 13. a(j) == a_in(j) * a_in(j) ⊥e 12

26 }

27 14. 0 ≤ j ∧ j < x → a(j) == a_in(j) * a_in(j) →i 8

28 }

29 15. ∀i: (0 ..< x) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i) ∀i 6

30 16. {

31 17. j: Z

32 18. {

33 19. x ≤ j ∧ j < a.size assume

34 20. x ≤ j ∧e1 19

35 21. j < a.size ∧e2 19

36 22. a(j) == a_in(j) algebra 1 2 20 21

37 }

38 23. x ≤ j ∧ j < a.size → a(j) == a_in(j) →i 18

39 }

40 24. ∀i: (x ..< a.size) a(i) == a_in(i) ∀i 16 }"""

41

42 while (x != a.size) {

43 l"""{ invariant ∀i: (0 ..< x) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i)

44 ∀i: (x ..< a.size) a(i) == a_in(i)

45 0 ≤ x

46 x ≤ a.size

47 modifies x, a }"""

48

49 l"""{ 1. ∀i: (0 ..< x) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i) premise

50 2. ∀i: (x ..< a.size) a(i) == a_in(i) premise

51 3. 0 ≤ x premise

52 4. x ≤ a.size premise

53 5. x ≠ a.size premise

54 6. x < a.size algebra 4 5 }"""

55

56 a(x) = a(x) * a(x)

57

58 l"""{ 1. a(x) == a_old(x) * a_old(x) premise

59 2. ∀i: (0 ..< x) a_old(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i) premise

60 3. ∀i: (x ..< a_old.size) a_old(i) == a_in(i) premise

61 4. a.size == a_old.size premise

62 5. x < a_old.size premise

63 6. x < a.size subst2 4 5

64 7. ∀i: (x ..< a.size) a_old(i) == a_in(i) subst2 4 3

65 8. x ≤ x ∧ x < a.size → a_old(x) == a_in(x) ∀e 7 x

66 9. x ≤ x algebra

67 10. x ≤ x ∧ x < a.size ∧i 9 6

68 11. a_old(x) == a_in(x) →e 8 10

69 12. a(x) == a_in(x) * a_in(x) subst1 11 1

70 13. ∀q_i: (0 ..< a.size)

71 q_i ≠ x → a(q_i) == a_old(q_i) premise

72 14. {

73 15. j: Z

74 16. 0 ≤ j ∧ j < a.size →

75 (j ≠ x → a(j) == a_old(j)) ∀e 13 j

76 17. {

77 18. 0 ≤ j ∧ j ≤ x assume

78 19. 0 ≤ j ∧ j < x →

79 a_old(j) == a_in(j) * a_in(j) ∀e 2 j

80 20. 0 ≤ j ∧e1 18

81 21. j ≤ x ∧e2 18

82 22. {

83 23. j < x assume

84 24. 0 ≤ j ∧ j < x ∧i 20 23

85 25. a_old(j) == a_in(j) * a_in(j) →e 19 24

86 26. j < a.size algebra 23 6

87 27. j ≠ x algebra 23

88 29. 0 ≤ j ∧ j < a.size ∧i 20 26

89 30. j ≠ x → a(j) == a_old(j) →e 16 29

90 31. a(j) == a_old(j) →e 30 27

91 32. a(j) == a_in(j) * a_in(j) subst2 31 25

92 }

93 33. {

94 34. j == x assume

95 35. a(j) == a_in(j) * a_in(j) subst2 34 12

96 }

97 36. a(j) == a_in(j) * a_in(j) ∨e 21 22 33

98 }

99 37. 0 ≤ j ∧ j ≤ x → a(j) == a_in(j) * a_in(j) →i 17

100 }

101 38. ∀i: (0 .. x) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i) ∀i 14

102 39. 0 ≤ x premise

103 40. {

104 41. j: Z

105 42. 0 ≤ j ∧ j < a.size →

106 (j ≠ x → a(j) == a_old(j)) ∀e 13 j

107 43. {

108 44. x + 1 ≤ j ∧ j < a.size assume

109 45. x + 1 ≤ j ∧e1 44

110 46. j < a.size ∧e2 44

111 47. 0 ≤ j algebra 45 39

112 48. j ≠ x algebra 45

113 49. 0 ≤ j ∧ j < a.size ∧i 47 46

114 50. j ≠ x → a(j) == a_old(j) →e 42 49

115 51. a(j) == a_old(j) →e 50 48

116 52. x ≤ j ∧ j < a.size →

117 a_old(j) == a_in(j) ∀e 7 j

118 53. x ≤ j algebra 45

119 54. x ≤ j ∧ j < a.size ∧i 53 46

120 55. a_old(j) == a_in(j) →e 52 54

121 56. a(j) == a_in(j) subst1 55 51

122 }

123 57. x + 1 ≤ j ∧ j < a.size → a(j) == a_in(j) →i 43

124 }

125 58. ∀i: (x + 1 ..< a.size) a(i) == a_in(i) ∀i 40 }"""

126

127 x = x + 1

128

129 l"""{ 1. x == x_old + 1 premise

130 2. 0 ≤ x_old premise

131 3. x_old < a.size premise

132 4. ∀i: (0 .. x_old) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i) premise

133 5. ∀i: (x_old + 1 ..< a.size) a(i) == a_in(i) premise

134 6. 0 ≤ x algebra 1 2

135 7. x ≤ a.size algebra 1 3

136 8. ∀i: (x ..< a.size) a(i) == a_in(i) subst2 1 5

137 9. {

138 10. j: Z

139 11. 0 ≤ j ∧ j ≤ x_old →

140 a(j) == a_in(j) * a_in(j) ∀e 4 j

141 12. {

142 13. 0 ≤ j ∧ j < x assume

143 14. 0 ≤ j ∧e1 13

144 15. j < x ∧e2 13

145 16. j ≤ x_old algebra 15 1

146 17. 0 ≤ j ∧ j ≤ x_old ∧i 14 16

147 18. a(j) == a_in(j) * a_in(j) →e 11 17

148 }

149 19. 0 ≤ j ∧ j < x → a(j) == a_in(j) * a_in(j) →i 12

150 }

151 20. ∀i: (0 ..< x) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i) ∀i 9 }"""

152 }

153 l"""{ 1. ∀i: (0 ..< x) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i) premise

154 2. not (x != a.size) premise

155 3. x == a.size algebra 2

156 4. ∀i: (0 ..< a.size) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i) subst1 3 1 }"""

157}

You are not expected to understand the above, but the function’s

post-condition list the guarantees of what goes out for any given

array of integers.

In this case, “what goes out” is an array whose elements are squared –

it is guaranteed to work, because it was analyzed the same way an electronics

engineer analyzes a circuit.

If the above somehow looks daunting, here is a shorter proof that leverages Logika’s automation:

3def square(a: ZS): Unit = {

4 l"""{ modifies a

5 post ∀i: (0 ..< a.size) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i) }"""

6

7 var x: Z = 0

8

9 while (x != a.size) {

10 l"""{ invariant ∀i: (0 ..< x) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i)

11 ∀i: (x ..< a.size) a(i) == a_in(i)

12 0 ≤ x

13 x ≤ a.size

14 modifies x, a }"""

15

16 a(x) = a(x) * a(x)

17

18 l"""{ 1. x < a.size auto

19 2. ∀i: (0 .. x) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i) auto

20 3. ∀i: (x + 1 ..< a.size) a(i) == a_in(i) auto }"""

21

22 x = x + 1

23 }

24}

Even better, using symbolic execution, it can be automatically proved without proof annotations:

3def square(a: ZS): Unit = {

4 l"""{ modifies a

5 post ∀i: (0 ..< a.size) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i) }"""

6

7 var x: Z = 0

8

9 while (x != a.size) {

10 l"""{ invariant ∀i: (0 ..< x) a(i) == a_in(i) * a_in(i)

11 ∀i: (x ..< a.size) a(i) == a_in(i)

12 0 ≤ x

13 x ≤ a.size

14 modifies x, a }"""

15

16 a(x) = a(x) * a(x)

17

18 x = x + 1

19 }

20}

This note was adapted from David Schmidt's CIS 301, 2008, Chapter 00 course note.